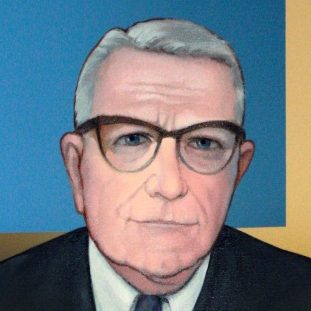

Hon. John Oliver Henderson

Dates of Service: 1959-1974

Born November 13, 1909, in Buffalo, NY

Died February 19, 1974

Federal Judicial Service:

- Judge, U.S. District Court for the Western District of New York

- Nominated by Dwight D. Eisenhower on August 21, 1959, to a seat vacated by Justin C. Morgan. Confirmed by the Senate on September 14, 1959, and received commission on September 21, 1959. Served as chief judge, 1967-1974. Service terminated on February 19, 1974, due to death.

Education:

- University of Buffalo Law School, LL.B., 1933

Professional Career:

- U.S. Army lieutenant colonel, 1942-1946

- Private practice, Buffalo, New York

- Clerk, Erie County [New York] Surrogate’s Court, 1947-1948

- U.S. attorney for the Western District of New York, 1953-1959

Noteworthy Cases and Other Information

(written by Hon. John T. Curtin)[1]

Lawyers who practiced before Judge Henderson recall him as a man of great stature, both professionally and physically. At 6’4″ and 260 pounds, he loomed over courtroom proceedings, his booming voice intimidating the uninitiated. One lawyer recalled that Judge Henderson seemed to span the distance between the doorway of his chambers and bench in just three steps.

Judge Henderson prided himself on being able to reduce complicated issues to simple truths. When a lawyer at a suppression hearing sought to introduce a Cheektowaga town ordinance regarding a railroad detective’s curbside inspection of his client’s garbage, Judge Henderson remarked, “What does the ordinance say? ‘Thou shalt not pick garbage or nits?'”

Judge Henderson presided over many important and dramatic cases. He sat on the three-judge panel which ruled that Senator Robert Kennedy’s appointed successor could fill the two and one-half years remaining of his term and that the office did not have to be placed on the ballot sooner.[2] He also handled important cases involving race discrimination in employment at Bethlehem Steel[3] and many cases arising from the Attica prison riots.

In the early 60s, Black Muslim inmates at Attica State Prison brought a civil rights action alleging that prison practices infringed on their religious rights. Judge Henderson exercised restraint and chose to abstain, finding it appropriate that State authorities first address those rights. The Circuit Court agreed. [4] However, when the response by prison authorities proved slow, his ensuing order that they act quickly was heeded, and the principal issues in the case were thereby resolved.[5]

It is a common occurrence in our district for the judges to be called upon to resolve questions of Indian law. The Seneca Nation and the Tuscaroras both have large reservations within the district. In Judge Henderson’s case, he had to decide whether the United States had the power to sanction the taking of Seneca Nation land for a four-lane highway in face of the treaty of 1774 between the Seneca Nation and the United States. The taking was part of the Allegany reservoir project in which replacement of highways was an approved part of the project. By prior decision, the government had acquired the right to flowage easements on the reservations, but in this case, the Secretary of the Army, at the request of the State of New York, had provided for the taking of land for a four-lane highway instead of the two-lane highway which was in place before the project began. The Seneca Nation claimed that congressional delegation of this authority to the Secretary was not clear enough. Judge Henderson’s decision approving the taking was controversial and widely criticized but approved by a two-to-one Court of Appeals vote.[6]

Those who practiced in his court enjoyed his sharp wit and irrepressible humor. Outside the courtroom, Judge Henderson was a favorite of attorneys and reporters and was always willing to sit down to explain a technical point of law to a novice reporter on the courtroom beat.

Nevertheless, he insisted on courtroom decorum. When defendants in draft evasion cases called him names and refused to stand when court commenced, they were, at an appropriate time after the jury verdict, cited for contempt of court and sentenced to jail.

Judge Henderson had many interests, including trout fishing, collecting antique steam engines, and gardening. He enjoyed bird-watching and rock-hunting with his wife. When a battery of attorneys petitioned the court for injunctive relief to prevent the construction of a bridge across Lake Chautauqua, he advised the attorneys for all parties that he was a non-active member of the plaintiff Audubon Society, explaining: “Apparently, a family membership costs only five dollars more than an individual membership, and Mrs. Henderson could not pass up the bargain.” When the attorneys for all parties stated that they would waive any objection, he noted the allegations of the complaint that the bridge construction would have an adverse impact on the trout in Lake Chautauqua and said: “Gentlemen, I must advise you: there are no trout in Lake Chautauqua.”[7]

It is also interesting to note that our district was one of the first to have the blessing—or burden, depending upon your point of view—of having the Strike Force concept in place. In late 1967, one of the earliest Strike Force prosecutions against major underworld figures in Western New York was presided over by Judge Henderson. Only conspiracy counts under the Hobbs Act were involved in that case, since there was no charge that the substantive crimes were consummated. Not generally inclined to lecture defendants, he often said, “The sentence speaks for itself.” To the five defendants in that case, the three 20-year and two 15-year sentences said much.[8]

In some ways, Judge Henderson was an old-fashioned judge—he even made house calls. On December 12, 1968, Judge Henderson drove to the Town of Lewiston, near Niagara Falls, where he arraigned reputed Mafia leader Stefano Magaddino at the 77-year old man’s bedside. Magaddino pleaded not guilty to gambling conspiracy charges during a two and one-half-minute arraignment. Magaddino, who had been named as the head of the regional Cosa Nostra, was examined by several heart specialists, all of whom agreed that he could not survive the stress of trial. Twenty months after his arrest, Judge Henderson ruled that Magaddino could not withstand the stress of trial and had only “months to live.” No one would have enjoyed the irony more than Judge Henderson that Stefano Magaddino outlived him by six months.[9]

Judge Henderson died in office on February 18, 1974, at the age of 64, when presiding at a complicated criminal conspiracy case.