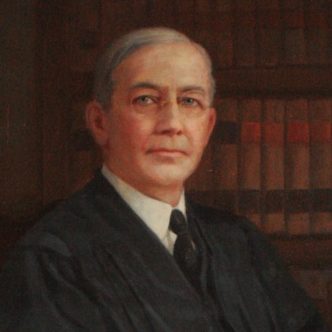

Hon. John Knight

Dates of Service: 1931-1955

Born April 29, 1871, in Arcade, NY

Died June 15, 1955

Federal Judicial Service:

- Referee in Bankruptcy, Western District of New York, 1899-1904

- Judge, U.S. District Court for the Western District of New York

- Received a recess appointment from Herbert Hoover on March 18, 1931, to a seat vacated by John R. Hazel; nominated to the same position by Herbert Hoover on December 15, 1931. Confirmed by the Senate on January 6, 1932, and received commission on January 9, 1932. Served as chief judge, 1948-1955. Service terminated on June 15, 1955, due to death.

Education:

- University of Rochester, A.B., 1893

- Read law, 1896

Professional Career:

- Town clerk, Arcade, New York, 1892-1896

- Private practice, Arcade, New York, 1896-1900

- District attorney, Wyoming County, New York, 1904-1913

- State assemblyman, New York, 1913-1917

- State senator, New York, 1917-1931; president pro tem, 1924-193

Noteworthy Cases and Other Information

(written by Hon. John T. Curtin)[1]

While on the federal bench, Judge Knight made headlines throughout the country in 1952 when he denied an application by the Italian government to extradite Carl G. LoDolce of Rochester. Mr. LoDolce, a former O.S.S. sergeant, was charged with the murder of Major William V. Hollihan while they both were on a secret mission behind German lines in Northern Italy during World War II. Judge Knight ruled that during a time of war, the United States Army had exclusive jurisdiction over its own soldiers in occupied territory. The Army lost jurisdiction when it gave LoDolce an honorable discharge. Under these circumstances, he decided that the Italian court could not compel extradition for LoDolce to stand trial.[2]

Judge Knight’s courage was also reflected in other rulings. On December 12, 1952, he issued an 80-day injunction under the Taft Hartley Act ordering 1,500 strikers back to work in the American Locomotive Company Plant in Dunkirk. They had walked out three months earlier, tying up production on nickel plate needed by the Atomic Energy Commission for the production of weapons. The Judge held that the strike was, in effect, a strike against the government and, as such, illegal.[3]

The strikers returned to their jobs, and contract negotiations resumed. The C.I.O bypassed the Circuit Court of Appeals and challenged Judge Knight’s ruling directly in the United States Supreme Court.[4] However, the plaintiffs withdrew their appeal upon reaching a new contract, thus eliminating the strike threat.

Judge Knight’s capacity for detail served him well during his time on the bench. He was often called upon to adjudicate some of the ramifications of early New Deal federal laws. Typical was one which involved priority for payment of federal social security taxes and State unemployment taxes from the estate of a bankrupt citizen. The formula he developed to deal with this problem was upheld by the United States Supreme Court.[5]

Judge Knight loved the country. Throughout his career, he conducted a term in the city of Jamestown, which is located at the easterly end of Lake Chautauqua. At the conclusion of each daily session, most of the lawyers and court personnel would travel to the Lenhart Hotel, located about ten miles away at the midpoint in the lake at the Stowe Ferry landing. The Lenhart was a solid wooden structure with a long porch and traditional rocking chairs. These surroundings helped give the Judge and others special insight into the problems before the court. Mosquito control was provided by large birdhouses set at the ferry landing. Although a modern bridge now provides speedy crossing of the lake at that point, the hotel and ferry landing still remain, but, alas, the Jamestown term has been pretermitted by an unduly efficient chief judge whose identity shall remain unstated.

Judge Knight did not follow Judge Hazel’s lead and retire at age 70. Becoming a judge at age 60, he continued to serve until he died at age 84 in 1955.

Throughout his judicial life, he was a dauntless commuter. He drove almost daily from his home in Arcade, about 40 miles from the courthouse, over bumpy country roads, during years when most people would look upon such a journey as a major expedition.

Other Cases of Note

Judge Knight was “considered an authority on patent-infringement cases.”[6] As an example, in a case regarding plastic plugs and caps, he studied twenty-five patents before issuing a permanent injunction.[7]