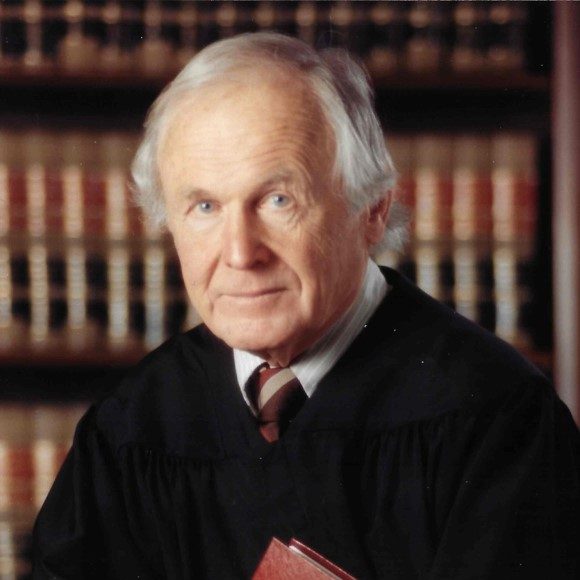

Hon. John T. Curtin

Judge Curtin was born on August 24, 1921 to John and Ellen Curtin. His father worked at Bethlehem Steel, and his family lived in South Buffalo.

After graduation from Canisius High School, Judge Curtin enrolled in Canisius College but left in 1942 to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps. He served in World War II as a pilot and achieved the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He flew 35 combat missions and survived a crash landing in the Pacific.

After the war, Judge Curtin returned to Canisius College, receiving a B.S. in 1946. In 1949, he received his LLB from University of Buffalo Law School. Asked what prompted him to pursue a legal career, he recounted that a lawyer lent his car to him and several servicemen for an evening out when they were stationed in Minneapolis. Judge Curtin was so appreciative of this man’s generosity that he decided that he would apply to law school.

Judge Curtin worked in private practice from 1949 until 1952, and 1954 until 1961. From 1952 to 1954, he served in the Marine Corps Reserve. In 1961, he was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Western District of New York. On December 14, 1967, Judge Curtin was named to a new seat on the Western District bench. He served as Chief Judge from 1974 to 1989, and assumed senior status on July 1, 1989.

Judge Curtin’s numerous contributions on the bench were significant. Following the 1971 Attica uprising, Judge Curtin was confronted with applications for injunctive relief to protect the rights of the inmates and prevent reprisals. Over the succeeding months and years, the judges faced a flood of prisoner pro se petitions seeking habeas corpus and civil rights remedies. In 1974, upon the death of Judge Curtin’s colleague, Hon. John O. Henderson, a huge backlog of these cases remained. To address it, Chief Judge Curtin created the District’s first Pro Se Law Clerk position, and the cases were resolved within a year.

In 1976, in the case of Arthur v. Nyquist, Judge Curtin determined that the Buffalo public schools were “deliberately segregated” and directed that desegregation efforts begin immediately. He spent many hours with the parties hashing out inventive plans that included magnet schools and a complex busing structure. His plan was copied by other school districts across the country.

Judge Curtin presided over the United States v. City of Buffalo discrimination cases, involving both the Police and Fire Departments, ordering one-for-one hiring. He also handled the historic Love Canal case, and the District’s first death penalty drug case, United States v. Darryl Johnson.

Another famous case was The Buffalo Five trial, involving the 1971 arrests of five individuals for breaking into Buffalo’s old Post Office in an attempt to burn draft records. After guilty verdicts, Judge Curtin sentenced each defendant to a one-year suspended sentence. Forty-four years later, one of the defendants traveled almost 400 miles to thank Judge Curtin for his compassion. During their meeting, Judge Curtin observed, “I always believed there should be a chance for a second chance, and the opportunity to have a good life.”

Asked to identify his “favorite” case, Judge Curtin replied – the Kennedy Park Homes case. In 1970, he issued a 93-page decision, ruling that the City of Lackawanna had discriminated against African-Americans in blocking the construction of 138 low income homes in a nearly all-white neighborhood. Judge Curtin dismissed as “mere rationalization” the City’s contention that the sewer system in the neighborhood could not support additional homes. He ordered the City to take “whatever action is necessary to provide adequate sewage service” to the subdivision. His decision was affirmed by the Court of Appeals, and a writ of certiorari was denied.

After Judge Curtin assumed senior status, he chose to refrain from taking criminal drug cases because of the mandatory Sentencing Guidelines. He openly proclaimed his dissatisfaction regarding the treatment of defendants who were convicted of drug offenses and was an early advocate of the eventual decriminalization of marijuana.

Judge Curtin received numerous distinguished awards during his lifetime. Following his death, the Erie County Bar Association created the John T. Curtin Profiles in Courage Award in his honor, and he was its first recipient, posthumously. Despite the controversial cases he ruled upon, his personal phone number and home address were listed in the local telephone book. He felt strongly that, as a civil servant, he should remain accessible to the public, and his chambers door was always open.

Judge Curtin married Jane Good Curtin in 1952, and they had seven children. He was very active throughout his life. For example, he was an avid runner, who ran many marathons and continued running into his early eighties.

Throughout his career, Judge Curtin’s chambers, which included 35 law clerks over 48 years, was an extension of his family. Early on Judge Curtin established a tradition in which he and his active clerks lunched together on most days. Former and current clerks gathered for bigger parties to celebrate many occasions. They remained inextricably connected to Judge Curtin because of the indelible mark he had on their careers and, more importantly, their “psyches and souls.” He had just two secretaries, and he encouraged his last secretary to attend law school – a challenge she met.

Judge Curtin remained on the bench until April 12, 2016, when he retired because of diminishing health. He passed away one year later on April 14, 2017, at the age of 95.

***

This memorial was prepared with the assistance and contributions of Judge Curtin’s longtime secretary, Janet Curry, and a number of his former law clerks.