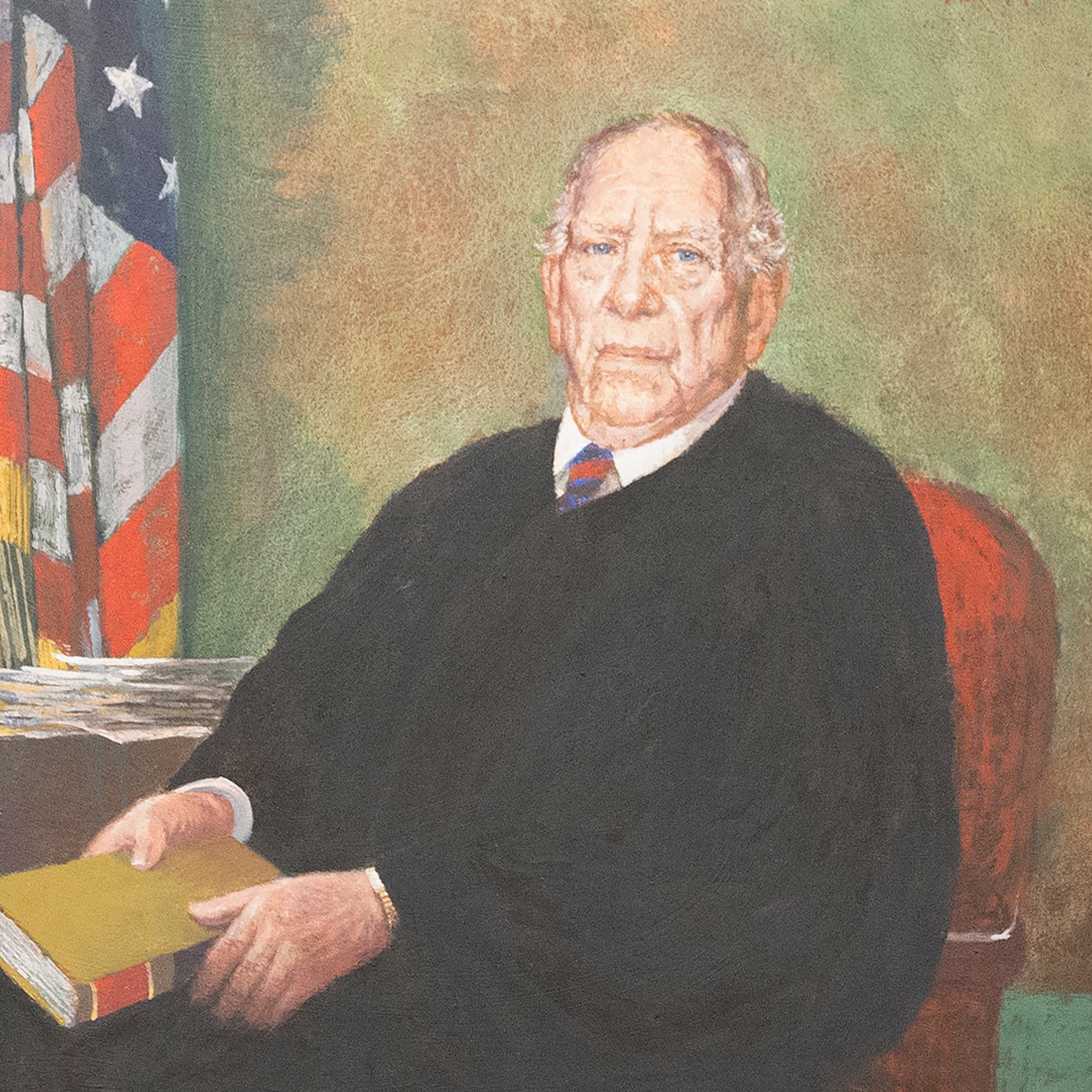

Hon. Harold P. Burke

Dates of Service: 1937-1981

Born June 6, 1895, in Rochester, NY

Died July 17, 1981, in Rochester, NY

Federal Judicial Service:

Judge, U.S. District Court, Western District of New York

Nominated by Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 27, 1937, to a seat vacated by Harlan W. Rippey. Confirmed by the Senate on June 15, 1937, and received commission on June 18, 1937. Served as chief judge, 1955‑1967. Assumed senior status on June 15, 1981. Service terminated on July 17, 1981, due to death.

Education:

Notre Dame Law School, LL.B., 1916

Professional Career:

U.S. Army

Private practice, Rochester, New York, 1920‑1931

Assistant attorney general, New York, 1931‑1934

Corporate counsel for Rochester, New York, 1934‑1937

Noteworthy Cases and Other Information:

(written by Hon. John T. Curtin)[1]

The early winter of 1959…had been a heavy one with much snow and ice. After dumping snow on the city for weeks, the weather changed suddenly in the third week in January. Heavy rain storms and thaw set in. On the evening of January 21, the sudden thaw began to melt the ice on the lake and the Buffalo River, which winds through the port area of Buffalo. The river is lined with docks, old grain elevators and factories, eventually emptying into Lake Erie. Unfortunately that night, moorings of some of the grain boats were not as snug as they should have been.

The S.S. MacGilvray Shiras, owned by Kinsman Transit, was not able to withstand the press of ice and debris and, at about 10:40 that evening, broke loose. It smashed into the S.S. Michael K. Tewksbury, sending both vessels downstream. Not expecting any traffic, the operators of the Michigan Avenue lift-bridge had taken a tavern break on that nasty winter evening. Frantic phone calls to warn them went unheeded until the very last moment. The bridge was just being raised when the Shiras and the Tewksbury crashed into its center at about 11:17. In the course of their downstream journey, several other vessels were damaged. The pileup at the bridge caused the ice and debris to back up several miles along the course of the river, causing extensive damage to waterfront property and disrupting transportation on the river for about two months. Assessing liability and damage became the subject of drawn out and difficult litigation before Judge Harold. P. Burke. He found that while most of the damage may have been unexpected, it was not unforeseeable. His decision was affirmed and modified by the Court of Appeals. Judge Friendly’s appellate opinion in that case has since become the standard text in many law schools on the problem of foreseeability…[2]

Judge Burke was a study in contrasts. Off the bench, he was cordial, charming, an avid fisherman, and raconteur. On the bench, his style was terse, blunt, and to the point. If lawyers had prepared their cases well, they got on famously with him. But, if an attorney appeared in his court unprepared, the welcome was either frosty or blistering, depending upon the Judge’s attitude on that particular day. There were no favorites. Lawyers from large firms or the government were treated the same as anyone else.

Jury trials were his stock in trade. His courtroom hours were long, and if he believed that a lawyer needed additional time with a witness, he would simply skip the lunch hour and proceed right into the afternoon session. His charges were models of clarity and conciseness. There was hardly an attorney, including the present writer, who did not feel his wrath from time to time, but upon reflection, the victim would usually conclude that the Judge was in the right.

In spite of his crusty courtroom manner, Judge Burke believed deeply in the value of probation, and few sentences of his may be considered lengthy.

During the late 1940s and through the 1950s, the burden on Judge Burke was an extremely heavy one. In 1940, during Judge Knight’s declining years, Judge Burke traveled to Buffalo often and handled many civil and criminal cases on the Buffalo calendar. Even after Judge Knight’s death in 1951, this extra burden continued because of the serious illness of Judge Morgan during the middle 1950s. For all practical purposes, for many years Judge Burke handled the entire calendar in our district. It was a very difficult and trying time. Only with the appointment of Judge Henderson in 1959 did the need for Judge Burke to journey to Buffalo diminish.

Judge Burke was unique in other respects as well. For most of his career on the bench, he eschewed the services of a law clerk. He said, “All they did was give me more briefs. I have enough of them as it is.” As a result, his written opinions were brief and seldom reported. When asked about reversals by the Court of Appeals, Burke replied, “I never feel badly about it, I always feel that is what we have the Court of Appeals for.”

Throughout his career, Judge Burke presided at the trial of many difficult criminal and civil cases, such as the Kinsman ship collision case, which has already been mentioned. In one notable criminal case, the defendant, a longtime member of the Communist party, was convicted for violation of the Smith Act after a jury trial. As you may recall, the Smith Act outlawed membership in organizations advocating the overthrow of the government by force or violence. The Second Circuit affirmed, finding “a clear and present danger” of violent overthrow of the government, but in 1961, Noto’s conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court, which held that there was insufficient evidence to convict. To paraphrase Judge Burke, that is what we have the Supreme Court for.[3]

Although, as I have pointed out, Judge Burke often had a chilly demeanor on the bench, he was practical and very attentive to the rights of individuals who appeared before him. I recall one trial in which the defendants styled themselves as the “Flower City” conspiracy. This case arose in the early 1970s when a group protesting the Vietnam War broke into the Selective Service Offices in Rochester and were caught strewing the records about. Some of the defendants decided to proceed pro se. Every morning they would bring in fresh flowers and place them on counsel’s table, on the clerk’s bench, and occasionally on the Judge’s bench before he appeared. He was addressed by the group as Mister, instead of “Judge” or “Your Honor.” Burke appeared not to notice the flowers nor the informal address by the litigants. The trial, which could have erupted into protest and demonstrations, proceeded smoothly to the ultimate conclusion of conviction. The Judge’s sentence, as usual, was fairly mild, and he proceeded briskly to other business.[4]

In his off hours, he was [an] avid fisherman. One of his fishing companions described the Judge as “the kind of fisherman who will cut the barbs off the end of the hook to make it sportier.” Judge Burke had the distinction of being one of the longest active judges in the country, serving…44 years.